Publication

- Title: Tenecteplase versus standard medical treatment for basilar artery occlusion within 24 h (TRACE-5): a multicentre, prospective, randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoint, superiority, phase 3 trial

- Acronym: TRACE-5

- Year: 2026

- Journal published in: The Lancet

- Citation: Xiong Y, Alemseged F, Cao Z, et al. Tenecteplase versus standard medical treatment for basilar artery occlusion within 24 h (TRACE-5): a multicentre, prospective, randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoint, superiority, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2026; published online Feb 5.

Context & Rationale

-

Background

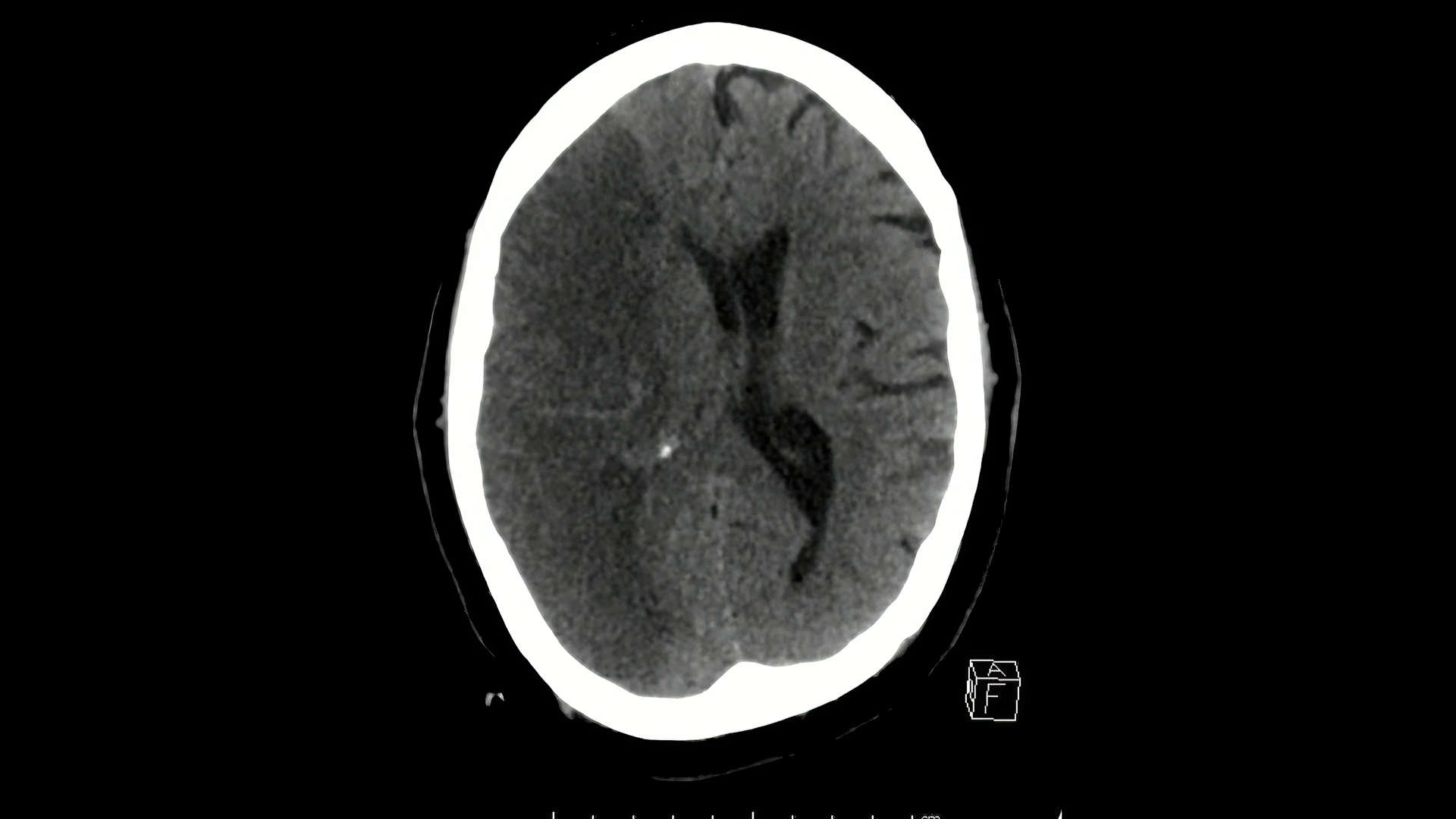

- Basilar artery occlusion (BAO) is a rare but devastating large-vessel occlusion with very high mortality and severe disability without recanalisation.

- Endovascular thrombectomy (EVT) improves outcomes for BAO up to 24 h in selected patients, but global access is limited; delays, transfer pathways, and affordability barriers mean many patients do not receive EVT.

- Tenecteplase is operationally attractive (single bolus) and has accumulating evidence as an alternative to alteplase, including signals of improved early reperfusion before EVT in BAO.

- Randomised evidence for IV thrombolysis specifically in imaging-confirmed BAO beyond 4·5 h and in pragmatic “EVT-variable” pathways has been scarce.

-

Research Question/HypothesisIn adults with near or complete BAO treated within 24 h, does IV tenecteplase (0·25 mg/kg; max 25 mg) improve 90-day excellent functional outcome compared with standard medical treatment (which could include alteplase within 4·5 h and usual antithrombotic strategies), with EVT permitted in both groups at clinician discretion?

-

Why This MattersDemonstrating effective and safe IV thrombolysis for BAO up to 24 h could broaden reperfusion access in settings with delayed, limited, or unaffordable EVT, and could potentially increase pre-EVT reperfusion in transfer pathways.

Design & Methods

- Research Question: Does IV tenecteplase within 24 h improve 90-day excellent functional outcome after BAO compared with pragmatic standard medical treatment?

- Study Type: Prospective, multicentre (66 stroke centres in China), randomised (1:1), open-label, blinded-endpoint, superiority, phase 3 trial.

- Population:

- Adults ≥18 years with posterior circulation ischaemic stroke symptoms due to near or complete BAO within 24 h of onset/last known well (or clinical deterioration/coma), confirmed on CTA or MRA.

- BAO definition: potentially retrievable occlusion, near occlusion (99% stenosis with string sign) or complete occlusion.

- Premorbid mRS ≤3.

- Imaging exclusions: intracranial haemorrhage/tumour; pc-ASPECTS <6 on non-contrast CT/CTA source images or DWI; significant cerebellar mass effect or acute hydrocephalus; established frank hypodensity suggesting subacute infarction; bilateral extensive brainstem ischaemia.

- Intervention:

- Tenecteplase 0·25 mg/kg (maximum 25 mg) as a single IV bolus over 5–10 seconds immediately after randomisation.

- Comparison:

- Standard medical treatment, which could include alteplase 0·9 mg/kg (max 90 mg) within 4·5 h, anticoagulation (e.g., heparin infusion), or antiplatelets, with or without EVT at clinician discretion in both groups.

- Blinding: Open-label treatment; outcome assessors and the Endpoint Adjudication Committee were masked to allocation.

- Statistics: Sample size 452 to detect a 12% absolute increase in mRS 0–1 (33% vs 21%) with 80% power at one-sided α=0·025 (5% attrition). Primary and dichotomous outcomes analysed with modified Poisson regression (robust SE) adjusted for age, baseline NIHSS, and onset-to-randomisation time (<6 h vs 6–24 h). Ordinal mRS (5–6 merged) analysed via ordinal logistic regression (proportional odds assumption tested). Intention-to-treat for efficacy and safety; prespecified per-protocol analysis. No interim analyses.

- Follow-Up Period: 90 days (mRS), with 24–36 h imaging for haemorrhage and 72 h early neurological endpoint.

Key Results

This trial was not stopped early. No interim analyses were planned or performed.

| Outcome | Tenecteplase (n=221) | Standard medical treatment (n=231) | Effect | p value / 95% CI | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary: mRS 0–1 or return to baseline mRS at 90 days | 83 (38%) | 66 (29%) | Adj RR 1.50 | 95% CI 1.09 to 2.08; P=0.014 | Adjusted for age, baseline NIHSS, onset-to-randomisation time (<6 h vs 6–24 h) |

| mRS 0–2 or return to baseline mRS at 90 days | 98 (44%) | 99 (43%) | Adj RR 1.16 | 95% CI 0.88 to 1.54; P=0.29 | Secondary |

| mRS 0–3 at 90 days | 114 (52%) | 123 (53%) | Adj RR 1.06 | 95% CI 0.82 to 1.37; P=0.66 | Secondary |

| Ordinal mRS at 90 days (mRS 5–6 merged) | 0: 36 (16%) 1: 43 (19%) 2: 17 (8%) 3: 18 (8%) 4: 25 (11%) 5–6: 82 (37%) |

0: 30 (13%) 1: 34 (15%) 2: 34 (15%) 3: 25 (11%) 4: 19 (8%) 5–6: 89 (39%) |

Adj common OR 1.51 | 95% CI 1.06 to 2.15; P=0.022 | Proportional odds assumption satisfied (Brandt test P=0.40) |

| Early clinical improvement at 72 h (NIHSS ↓≥8 or NIHSS 0–1) | 65 (29%) | 64 (28%) | Adj RR 1.08 | 95% CI 0.76 to 1.52; P=0.68 | Secondary |

| Substantial reperfusion at initial angiogram (eTICI 2B–3)* | 34/141 (24%) | 16/126 (13%) | Adj RR 1.90 | 95% CI 1.04 to 3.49; P=0.038 | Among those proceeding to DSA; *complete baseline occlusion subgroup |

| Safety: Symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage within 36 h (SITS-MOST) | 4 (2%) | 7 (3%) | Adj RR 0.58 | 95% CI 0.17 to 1.99; P=0.39 | All 7 sICH in control group had EVT; 1 received alteplase before EVT |

| All-cause mortality within 90 days | 65 (29%) | 71 (31%) | Adj RR 0.87 | 95% CI 0.62 to 1.22; P=0.41 | Safety |

| mRS 5–6 at 90 days | 82 (37%) | 89 (39%) | Adj RR 0.87 | 95% CI 0.65 to 1.18; P=0.38 | Safety |

| Any intracranial haemorrhage (post-hoc classification) | 26 (11.8%) | 14 (6.1%) | Adj RR 1.80 | 95% CI 0.93 to 3.46; P=0.079 | Post-hoc; includes 4 ICH beyond 36 h1 |

- Tenecteplase improved the prespecified “excellent outcome” endpoint (mRS 0–1/return to baseline) and shifted overall disability, but did not improve mRS 0–2 or mRS 0–3 dichotomies.

- Tenecteplase increased substantial reperfusion before thrombectomy among those undergoing angiography (24% vs 13%).

- Symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage and 90-day mortality were similar between groups.

Internal Validity

- Randomisation and Allocation: Central web-based randomisation with allocation concealment; stratified by intention for EVT and intention for alteplase; minimisation balanced age (≤70 vs >70), NIHSS (<10 vs ≥10), and onset-to-randomisation time (<6 h vs 6–24 h).

- Drop out or exclusions (post-randomisation): No missing primary/secondary outcomes. Protocol non-adherence occurred in 40/452 (9%), including crossover, alteplase use beyond 4·5 h, and inappropriate enrolment; prespecified per-protocol population was 210 vs 202 (tenecteplase vs control).1

- Performance/Detection Bias: Open-label treatment introduces potential performance bias; mitigated by masked outcome assessment and masked endpoint adjudication.

- Protocol Adherence / separation: Separation of the tested variable was clear (tenecteplase bolus vs no tenecteplase), but the comparator was intentionally heterogeneous: 80/231 (35%) received alteplase and other control therapies included antithrombotics and occasional heparin infusion.

- Baseline Characteristics: Groups were broadly balanced; median NIHSS 13 (7–25) vs 11 (6–21), median pc-ASPECTS 8 (6–8) vs 8 (7–8); ~49% underwent EVT overall (112/221 vs 110/231).

- Heterogeneity: Heterogeneous mechanisms (large-artery atherosclerosis predominated), time windows, and co-interventions (alteplase and EVT) likely diluted isolated drug effects but improved pragmatism.

- Timing: Median onset-to-randomisation 6.1 h vs 6.5 h; subgroup signal for 6–24 h was larger than <6 h (RR 2.51 vs 1.16), but interaction was not statistically significant (P=0.08).

- Separation of the Variable of Interest: EVT rates were similar (112/221 [50.7%] vs 110/231 [47.6%]); alteplase use occurred almost exclusively in control (80/231 [34.6%]) with 4 crossovers from tenecteplase group to control therapies (analysed ITT).

- Adjunctive therapy use: Reasons for not proceeding to EVT differed: neurological improvement/recanalisation 32/109 (29.4%) vs 24/121 (19.8%); patient/family refusal 24/109 (22.0%) vs 42/121 (34.7%). This imbalance could influence functional outcomes through differential EVT exposure and is addressed in post-hoc sensitivity analyses.1

- Statistical Rigor: Prespecified adjusted primary model was significant; post-hoc unadjusted ITT primary analysis was not (RR 1.31; 95% CI 0.95 to 1.82; P=0.10) and post-hoc adjustment for EVT refusal yielded RR 1.39; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.93; P=0.046, highlighting model sensitivity and post-randomisation complexity.1

Conclusion on Internal Validity: Moderate. Allocation concealment and blinded endpoint assessment are strengths, but open-label treatment, a heterogeneous comparator (including alteplase), and variable EVT delivery (including differential refusal) introduce performance and post-randomisation complexity that affect interpretability of a modest effect size.

External Validity

- Population Representativeness: Chinese multicentre population; large-artery atherosclerosis was the predominant mechanism (86% vs 82%), which may differ from other settings and could influence thrombolysis responsiveness and EVT complexity.

- Applicability: Highly relevant to systems with delayed/limited EVT access and transfer pathways, given single-bolus administration and lack of mandatory advanced imaging; generalisability to non-Asian populations and to centres with near-universal, rapid EVT is uncertain.

- Intervention availability: Tenecteplase formulation used was the same as in TRACE-2; formal comparability across formulations is not established in the trial report.

- Selection constraints: Excluded large baseline posterior circulation infarcts (pc-ASPECTS <6), significant mass effect/hydrocephalus, and extensive bilateral brainstem ischaemia; results do not apply to these higher-risk phenotypes.

Conclusion on External Validity: Moderate. Findings likely generalise to similar BAO populations within 24 h where EVT is delayed or variably delivered, but extrapolation beyond China, across stroke mechanisms, and into uniformly rapid EVT systems requires corroboration.

Strengths & Limitations

- Strengths:

- First phase 3 randomised evidence for tenecteplase in imaging-confirmed BAO up to 24 h with pragmatic co-interventions.

- Central allocation concealment; blinded outcome assessment and adjudication; no missing primary/secondary outcomes.

- Biologically plausible bridging signal (higher substantial reperfusion before EVT) aligned with clinical workflow relevance.

- Safety profile reassuring for sICH and mortality in a high-risk vascular territory.

- Limitations:

- Open-label design and heterogeneous control arm (alteplase in 35%; variable antithrombotic strategies).

- EVT delivered to only ~half despite EVT-capable sites; patient/family refusal was common and differed between groups, complicating causal attribution.

- Primary benefit concentrated in “excellent outcome” and ordinal shift; broader dichotomies (mRS 0–2, 0–3) were neutral.

- Generalisation outside China limited by differing stroke mechanisms, reimbursement structures, and tenecteplase formulations.

Interpretation & Why It Matters

-

Clinical implicationIn BAO within 24 h, tenecteplase increased the chance of excellent recovery (mRS 0–1/return to baseline) without excess sICH or mortality, supporting its use as a pragmatic reperfusion option when EVT is delayed, unavailable, or declined.

-

Bridging relevanceHigher pre-thrombectomy substantial reperfusion supports tenecteplase as a plausible bridging therapy, particularly in transfer pathways with longer thrombolysis-to-puncture intervals.

-

Outcome nuanceThe benefit signal is strongest for “excellent outcome” and mRS shift, while functional independence (mRS 0–2) was unchanged; clinical adoption may hinge on how systems value excellent recovery vs independence thresholds in this severe-stroke syndrome.

Controversies & Subsequent Evidence

- Comparator complexity and causal clarity: The “standard medical treatment” arm was intentionally heterogeneous (alteplase within 4·5 h, antiplatelets/anticoagulation), and EVT was discretionary in both arms; this improves pragmatism but reduces interpretability of tenecteplase versus alteplase specifically and of tenecteplase’s independent effect when EVT is reliably delivered.

- EVT uptake and refusal: Only ~half received EVT; patient/family refusal contributed meaningfully, and was more frequent in the control group among those not proceeding to EVT (34.7% vs 22.0%), introducing a plausible post-randomisation pathway to differential outcomes and motivating post-hoc adjustment for refusal.1

- Model dependence of primary benefit: The Lancet Comment highlighted that crude (unadjusted) ITT and per-protocol post-hoc analyses were not statistically significant for the primary and major secondary clinical endpoints, emphasising cautious interpretation of a modest effect dependent on the prespecified adjusted model.2

- Generalisability and formulation: The Comment noted that tenecteplase was a biosimilar formulation not authorised in some regions and that ethnic/aetiologic differences may limit extrapolation outside China; it also raised concerns about variable recruitment across sites (many low-enrolling centres) and potential representativeness implications.2

- Subsequent evidence trajectory: TRACE-5 sits alongside expanding evidence for tenecteplase in acute ischaemic stroke; ongoing BAO-focused work (e.g., POST-ETERNAL; planned IPD pooling) is intended to clarify tenecteplase’s role when EVT is intended and to refine selection in diverse populations.2

Summary

- TRACE-5 randomised 452 patients with CTA/MRA-confirmed near or complete BAO within 24 h to tenecteplase 0·25 mg/kg bolus (max 25 mg) vs pragmatic standard medical treatment (including alteplase within 4·5 h), with EVT allowed in both arms.

- Primary endpoint improved: mRS 0–1/return to baseline 38% vs 29% (Adj RR 1.50; 95% CI 1.09–2.08; P=0.014).

- Overall disability shifted favourably (Adj common OR 1.51; 95% CI 1.06–2.15; P=0.022), but mRS 0–2 and mRS 0–3 dichotomies were neutral.

- Substantial reperfusion before thrombectomy was higher with tenecteplase (24% vs 13%; Adj RR 1.90; 95% CI 1.04–3.49; P=0.038).

- Safety was similar for sICH and mortality; post-hoc “any ICH” was numerically higher with tenecteplase (11.8% vs 6.1%; P=0.079).

Further Reading

Other Trials

- 2022Tao C, Nogueira RG, Zhu Y, et al. Trial of endovascular treatment of acute basilar-artery occlusion. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(15):1361-1372.

- 2022Jovin TG, Li C, Wu L, et al. Trial of thrombectomy 6 to 24 hours after stroke due to basilar-artery occlusion. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(15):1373-1384.

- 2021Langezaal LCM, van der Hoeven EJRJ, Mont’Alverne FJA, et al. Endovascular therapy for stroke due to basilar-artery occlusion. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(20):1910-1920.

- 2020Liu X, Dai Q, Ye R, et al. Endovascular treatment versus standard medical treatment for vertebrobasilar artery occlusion (BEST): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(2):115-122.

- 2023Wang Y, Li S, Pan Y, et al. Tenecteplase versus alteplase in acute ischaemic cerebrovascular events (TRACE-2): a phase 3, multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2023;401(10377):645-654.

Systematic Review & Meta Analysis

- 2022Katsanos AH, Psychogios K, Turc G, et al. Off-label use of tenecteplase for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(3):e224506.

- 2024Palaiodimou L, Katsanos AH, Turc G, et al. Tenecteplase vs alteplase in acute ischemic stroke within 4.5 hours: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Neurology. 2024;103(9):e209903.

Observational Studies

- 2020Writing Group for the BASILAR Group. Assessment of endovascular treatment for acute basilar artery occlusion via a nationwide prospective registry. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(5):561-573.

- 2019Alemseged F, Di Giuliano F, Shah DG, et al. Response to late-window endovascular revascularization is associated with collateral status in basilar artery occlusion. Stroke. 2019;50(6):1415-1422.

- 2017Alemseged F, Shah DG, Diomedi M, et al. The basilar artery on computed tomography angiography prognostic score for basilar artery occlusion. Stroke. 2017;48(3):631-637.

- 2016van der Hoeven EJRJ, McVerry F, Vos JA, et al. Collateral flow predicts outcome after basilar artery occlusion: the posterior circulation collateral score. Int J Stroke. 2016;11(7):768-775.

- 2024Gerschenfeld G, Turc G, Obadia M, et al. Functional outcome and hemorrhage rates after bridging therapy with tenecteplase or alteplase in patients with large ischemic core. Neurology. 2024;103:e209398.

- 2025Rousseau JF, Weber JM, Alhanti B, et al. Short-term safety and effectiveness for tenecteplase and alteplase in acute ischemic stroke. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(3):e250548.

Guidelines

- 2026Prabhakaran S, Ruff I, Bernstein RA, et al. 2026 Guideline for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. Published online January 26, 2026.

- 2024Strbian D, Tsivgoulis G, Ospel J, et al. European Stroke Organisation and European Society for Minimally Invasive Neurological Therapy guideline on acute management of basilar artery occlusion. Eur Stroke J. 2024;9:835-884.

- 2021Berge E, Whiteley W, Audebert H, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines on intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. Eur Stroke J. 2021;6:I-LXII.

- 2023Alamowitch S, Turc G, Palaiodimou L, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) expedited recommendation on tenecteplase for acute ischaemic stroke. Eur Stroke J. 2023;8(1):8-54.

- 2019Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines. Stroke. 2019;50:e344-e418.

- 2025Xiong Y, Alemseged F, Cao Z, et al. Tenecteplase versus standard care in patients with acute basilar artery occlusion: trial protocol. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2025; published online Oct 28.

Notes

- *“Substantial reperfusion at initial angiogram” was assessed among patients with complete baseline occlusion undergoing DSA before thrombectomy; interpret as supportive mechanistic evidence rather than a whole-cohort efficacy endpoint.

Overall Takeaway

TRACE-5 is a landmark BAO thrombolysis trial because it tests single-bolus tenecteplase up to 24 h in an imaging-confirmed BAO population within a pragmatic, EVT-variable pathway. It demonstrated improved excellent functional outcome and an mRS shift without excess sICH or mortality, while highlighting the interpretive challenges of open-label care, heterogeneous comparators, and real-world EVT access and refusal.

Overall Summary

- Tenecteplase within 24 h improved the prespecified excellent outcome endpoint (38% vs 29%) and shifted disability distribution, with similar sICH and mortality

- Benefit did not extend to mRS 0–2 or mRS 0–3 dichotomies, and post-hoc analyses highlight sensitivity to model choice and EVT pathway factors

- Most applicable where EVT is delayed, unavailable, or variably delivered, and where single-bolus thrombolysis can be used in transfer pathways

Bibliography

- 1Xiong Y, Alemseged F, Cao Z, et al. Tenecteplase versus standard medical treatment for basilar artery occlusion within 24 h (TRACE-5): Supplementary appendix. Lancet. 2026; published online Feb 5.

- 2Tsivgoulis G, Palaiodimou L, Turc G. Intravenous tenecteplase for acute ischaemic stroke within 24 h due to basilar artery occlusion. Lancet. 2026;epublished February 5th.